¿Que te apetece leer?

Versión original

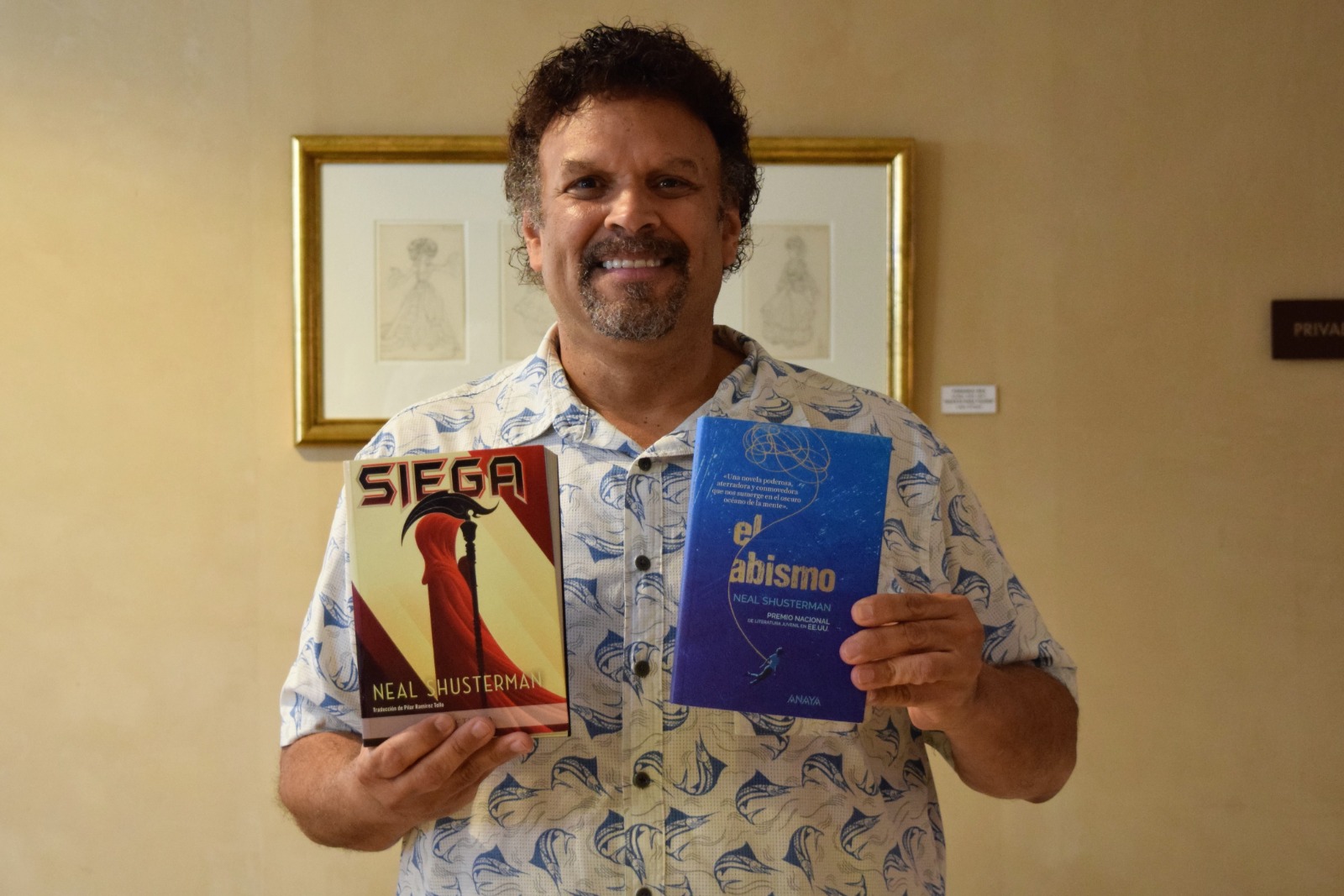

Neal Shusterman

El Templo #89 (agosto 2022)

Por Raquel Periáñez y Pablo G. Freire

518 lecturasWarning! There might be some light (light!) spoilers for The Toll here.

We first interviewed you in 2014, eight years ago. A lot has changed, and you’ve published a lot of books. How do you see the evolution of the YA market, and your evolution as an author?

That long ago? Wow. Well, it’s been exciting to watch the field of YA fiction grow and to be taken more seriously. I think there’s an awful lot of great things being written in the YA market and people have started to realize that. As far as my own books go, I like to think that I’m growing with everything that I write. One of the wonderful things about being a writer is that you’re always improving, you’re always growing, you’re always getting better, and part of that is challenging yourself as a writer to write things that break the mold, and try to do something different, something new, which is always what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to ask questions that may not have been asked before, or at least not asked before in the context of how I’m asking.

Your last novel, at least the last one published in Spain, Game Changer, has a very powerful concep t about the multiverse; literally changing your universe to change your point of view. How did you get to that approach and why did you think that was the right way to ask the questions you wanted to ask?

t about the multiverse; literally changing your universe to change your point of view. How did you get to that approach and why did you think that was the right way to ask the questions you wanted to ask?

Many times I’ll have an idea, a concept for a story, and it doesn’t connect with the reason to tell it. My original idea for Punto de inflexión (Game Changer), years ago, was the idea of an American football player who hit so hard he bounces into alternate dimensions. It was a fun idea, but there wasn’t anything important about it. It was only after I started to see what was going on in the world, and I started to connect the story with different social issues, and started to see that there’s a lot of people out there who are living privileged lives, who don’t understand their own privilege, and not necessarily are bad people, but they don’t understand what it’s like not to have that privilege, because they’ve had it all their lives. And I thought: what if this story is about this privileged kid who, through the series of the universes that he bounces into, finally gets to understand his privilege? And understand what it’s like to be persecuted because of your sexuality, or to be mistreated because you’re a woman; all of the different things that he has to face in the course of the story make him grow as an individual and he gets to see all of these perspectives. [That's] when I realized this wasn’t just a story about just someone bouncing into different universes, it was about understanding different social situations; that’s what made me want to write it. Now the story meant something, and it gave voice to a problem I felt it hadn’t been approached to this way.

And it’s more about the universes within our mind, and our internal universe is so limited by our own experiences. How can we get out of our own mental universe so that we can understand other people’s perspectives? All my books are about empathy. That’s one thing I think that it’s common in every single one of my books; it’s all about empathy.

And you used many different universes to talk about our own; it’s very different.

That’s what made me want to tell it, because it was different from any of the multiverse stories that we’ve seen. Because there’s so many multiverse stories; if I’m going to write something that there’s lots of stories in that same genre, it has to be something that is very different from the others.

Have you seen Everything Everywhere All At Once?

Yes, I have! I really loved it.

We’re super excited about Gleanings, the new book in the Arc of a Scythe series. How was it to work with other writers in a world that you’ve crafted for years?

I have done that once before, with a book called Unbound, which I’m not sure whether or not that one was published in the series Desconexión (Unwind); it’s the fifth one. I had the opportunity to write with writers that I wanted to write with, and it was a great experience. With that one, about half of the stories were written by me alone, and the other half were written by me with other writers. In Gleanings, there’s fourteen stories and five of them are co-written, and the rest are written by me. I’m involved with all of them, to different extents.

With the co-writers, the way that I work is: we’d come up with a concept together, and then we’d work out the other beats of what the story was going to be; they would write the first draft, I’d give them notes, like an editor, for revision, and then, after their revision comes back, then it becomes mine, then I rewrite it. So my biggest work comes after they’re done and then I do the revision that brings it to the voice that I feel the story needs to have to match the world.

Can you tell us anything about Gleanings, and what can we expect?

Well, the longest story in the book, which is pretty much a novella, it's almost its own little novel within the book, is about Scythe Goddard before he was Scythe Goddard, when he was just a teenager. And if you’ve read the other books, you know that his background is that he was on Mars, he was in the Mars colony and somehow involved with its destruction. Well, we get to see how that happened, and who he was before that happened, and everything leading up to that.

We get to see Scythe Curie, when she first becomes a Scythe, and she’s not respected, and not liked, until she does the audacious thing of gleaning the government, and suddenly that act puts her in people’s eyes as a much more powerful character. I sort of took readers through her decision to do that and how everything happens, so we see her when she was very young as well.

There’s a story about a dog, because a lot of fans ask “do pets get to live forever?” so I had a story that features a dog. And it’s co-written with a very good friend of mine. His specialty is writing animal stories, so I wanted him specifically to work on this one.

And there’s one that takes place here in Spain! In Barcelona. Scythe Dalí and Scythe Gaudí have a feud, and the story is about their feud. In the story, Scythe Gaudí… he’s more like a jedi, everybody loves him, and everybody hates Scythe Dalí. And that makes Dalí so angry, that he can’t get the respect that Scythe Gaudí gets. It’s a fun story, and it takes place throughout Barcelona. That one is co-written by my son Jarrod and his wife Sofía.

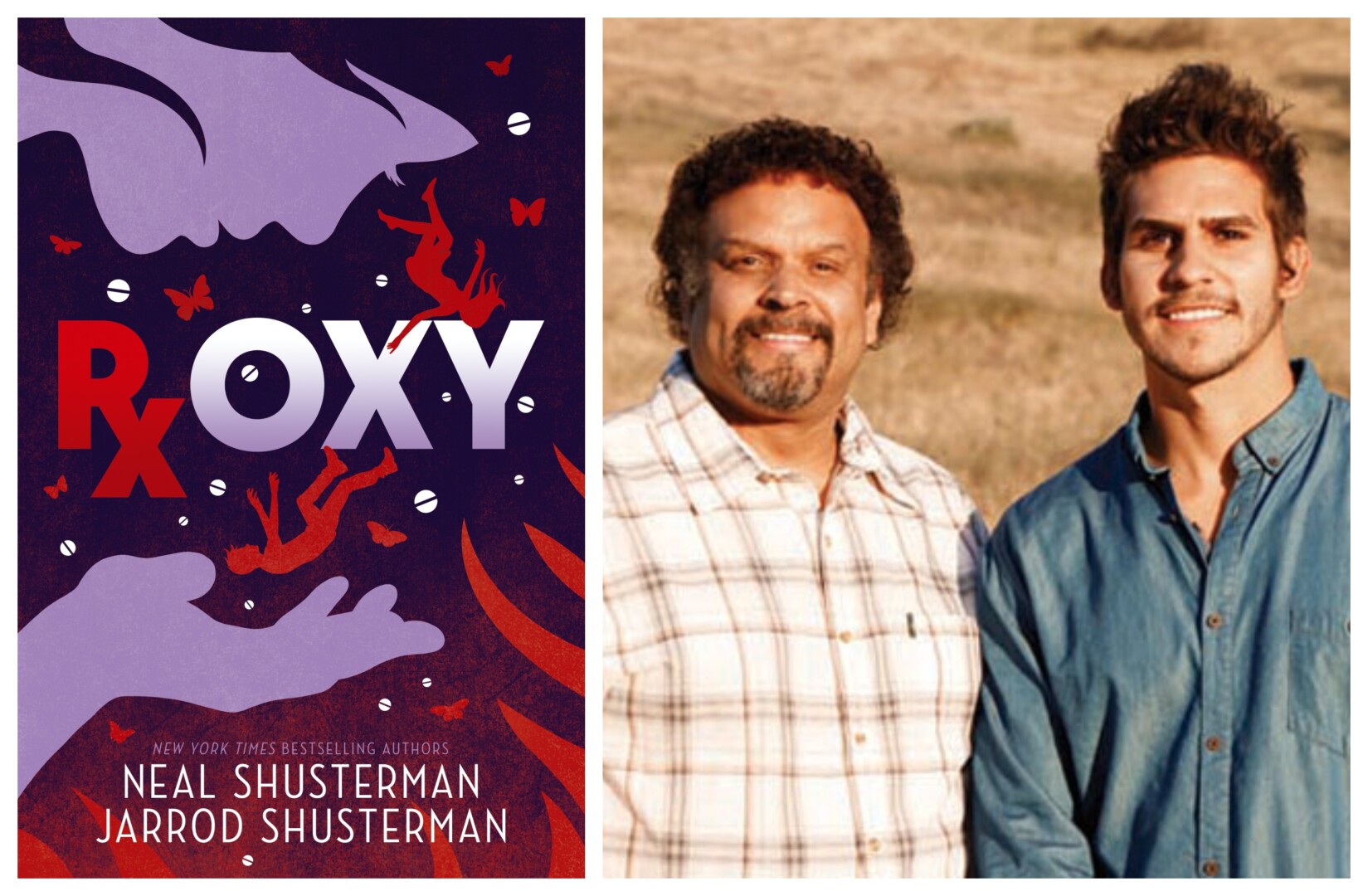

Speaking about your son, Jarrod, he’s also a writer, and he’s also your co-writer in Dry and Roxy, which hasn't come out here in Spain yet. How has it been to see him grow and evolve as a writer, but also working with him and trying to separate the personal from the professional?

Actually, that was easy. When we’re writing, we’re just collaborators. It's very professional, and it was really a bonding experience, because even like all fathers and sons we have disagreements, stuff going on, but when it comes to writing it’s like we turn that all off; we’re writers now. And it’s fine. So we never had arguments over writing, it was very professional, and it was a fantastic experience, both with Dry and with Roxy.

Actually, that was easy. When we’re writing, we’re just collaborators. It's very professional, and it was really a bonding experience, because even like all fathers and sons we have disagreements, stuff going on, but when it comes to writing it’s like we turn that all off; we’re writers now. And it’s fine. So we never had arguments over writing, it was very professional, and it was a fantastic experience, both with Dry and with Roxy.

Something that I learned early on in collaborations, in other collaborators that I’ve worked with, particularly Eric Elfman, with whom I co-wrote Tesla’s Attic… What came out of that collaboration was that we had a basic rule, and the rule was: both of us have to like it. So if anyone of us comes up with an idea the other one doesn’t like, no discussion, we don’t do it. We don’t try to fight for it, we don’t argue, we don’t get upset about it, it’s just the rule. If we don’t both don’t like it, then it doesn’t go in. And if we ever have a disagreement over if something should go in, what we end up doing is saying “ok, you think it should be this, I think it should be this, let’s come up with something better than both of those that we both love.” Every single time, we always came up with something that was better than each of us had individually, and then we just moved forward.

So I took that, that process, that way of working, and now every time I collaborate, it’s the same thing: we both have to agree, if we don’t agree we come up with something better. And I think it works when you’re working with someone who trusts you will come up with something better; and then we always do.

We wanted to ask you about Challenger Deep, because it’s your most different book, as it’s not science fiction. You used the concept of journey to talk about mental health, and how literature can help us in that journey. Why did you choose a more realistic approach?

It was almost the same as with Punto de inflexión (Game Changer), in that there is an issue that I wanted to address, and I thought the best way to address it was to take this character through a journey. It was also very personal, because the fantasy aspect, the dreamlike aspect of it, was all inspired by the artwork that my son did when he was struggling with mental illness (not Jarrod, my other son).

At one point, when he was really struggling, he was about sixteen years old at the time, and he said “I feel like I’m at the bottom of the ocean, screaming at the top of my lungs, and nobody can hear me”. And that idea of being so lost in your own mind that it’s as if you’re in the deepest place in the world and can’t get out… I wanted to be able to express what that felt like. I was not there; I could only empathize with him. I don’t know what it’s like to be down there, I wanted to try to understand that for him; and so, after he was feeling better, after he had sort of risen from the depths, and was finding himself again, I asked him if it would be okay if I could write this book. Not about him, but we would take a lot of the feelings he had, the experiences that he had, and we’d fold it in to this fictional story, and I would use his artwork to help inspire it. And he agreed, he thought that it would be a good idea to do that, and I put my heart and my soul into that book, more than any book that I’ve ever written. I’ve had so many people come up to me, and to him, and say that that book saved their life. To know that words, something that you wrote, has had that kind of positive influence on someone’s life… that’s more than any writer could dream of, to know that your work may have saved somebody’s life, your work impacted somebody else’s life for the better.

At one point, when he was really struggling, he was about sixteen years old at the time, and he said “I feel like I’m at the bottom of the ocean, screaming at the top of my lungs, and nobody can hear me”. And that idea of being so lost in your own mind that it’s as if you’re in the deepest place in the world and can’t get out… I wanted to be able to express what that felt like. I was not there; I could only empathize with him. I don’t know what it’s like to be down there, I wanted to try to understand that for him; and so, after he was feeling better, after he had sort of risen from the depths, and was finding himself again, I asked him if it would be okay if I could write this book. Not about him, but we would take a lot of the feelings he had, the experiences that he had, and we’d fold it in to this fictional story, and I would use his artwork to help inspire it. And he agreed, he thought that it would be a good idea to do that, and I put my heart and my soul into that book, more than any book that I’ve ever written. I’ve had so many people come up to me, and to him, and say that that book saved their life. To know that words, something that you wrote, has had that kind of positive influence on someone’s life… that’s more than any writer could dream of, to know that your work may have saved somebody’s life, your work impacted somebody else’s life for the better.

Dry is a terrifying read, because it’s so close to our actual reality. You wrote it before the pandemic; what do you think you got right about how society handles a big crisis? Do you look at it differently after these years?

It’s scary how close it was to the way people were raiding the supermarkets and fighting over water. The pandemic brought out the best in people, but also the worst in people. And that was the same thing with Dry. Human nature has a positive side and also a very selfish, negative side, and it was chilling to see how the pandemic reflected some of the things in Dry. But also, it’s been chilling to see how, in the area where Dry takes place, in Southern California, everything that’s happening there right now are exactly the things that happened in Dry leading up to it. How low the water levels are getting, how they keep trying to implement water saving measures that aren’t working, how people just still take for granted that when you turn on the water is going to come on. And they say in the history of the area the rivers have never been so low, particularly the Colorado river, which is the river that caused the problem in Dry; so to watch the real world imitating what we wrote and getting closer and closer to what happened in Dry is very frightening. It’s scary when your stories are prophetic, so I should write something that predicts something really happy now.

One of the most interesting things about the Arc of a Scythe series is that technology is not the enemy, but an ally; we always see sci-fi books where technology rises against humanity. It starts more like a utopia and slowly turns into a dystopia, but it’s our fault. Do you think humanity will always mess up?

Yes, we always see that! Exactly, it is our responsibility, if utopia is turning into dystopia is not because of artificial intelligence, it’s because of things that we’re doing. And well, humanity will always struggle with that. Ultimately, there are characters who fight that, and my stories are about hope, my stories are about seeing where the problems are and fighting those problems. If I made AI the problem, that would be putting the responsibility, our responsibility, somewhere else; it’s not the computers’ fault, it’s our fault. And Scythe was really a response to all of the dystopian stories that came out for the past ten, fifteen years. Teen dystopia wasn’t a genre when I wrote Desconexión (Unwind); it was one of the books that came out at the same time as The Hunger Games, Divergent, Maze Runner… All those books, and Desconexión (Unwind), they all came out at the same time, kind of created the genre.

Yes, we always see that! Exactly, it is our responsibility, if utopia is turning into dystopia is not because of artificial intelligence, it’s because of things that we’re doing. And well, humanity will always struggle with that. Ultimately, there are characters who fight that, and my stories are about hope, my stories are about seeing where the problems are and fighting those problems. If I made AI the problem, that would be putting the responsibility, our responsibility, somewhere else; it’s not the computers’ fault, it’s our fault. And Scythe was really a response to all of the dystopian stories that came out for the past ten, fifteen years. Teen dystopia wasn’t a genre when I wrote Desconexión (Unwind); it was one of the books that came out at the same time as The Hunger Games, Divergent, Maze Runner… All those books, and Desconexión (Unwind), they all came out at the same time, kind of created the genre.

After writing the five books in that series, I didn’t want to write another dystopia. Instead, I wanted to take the tropes and tear them apart, flip them, change them, and do something that we hadn’t seen. And I realized what we hadn’t seen was… not quite a utopian story, because ultimately, there really isn’t such thing as a utopia, we can never reach perfection; but what is the opposite of a dystopian story? That was the question that I asked myself. Well, dystopian stories are all about what happens when the world goes wrong, when we make poor choices and we’re stuck with these bad choices, and then create a world that is brought on by these wrong choices. What happens when we make the right choices? What happens when everything that we hoped for, everything that we want, we get? And I realized that even for the things that we want there are going to be consequences if we achieve them. So what are the consequences if we realize our dreams in medical science, if we realize our dreams in ending poverty, and ending war, and ending racism? What happens when all of those things come to past and we have created the world that we want? What are the consequences of that? And just following that thought, and doing a lot of research as to what our best-case scenarios are. There’s a lot of fear of AI, and rightfully so, but what are our hopes for it? If AI was everything we wanted it to be, what would that look like?

Thunderhead.

Thunderhead, exactly!! And one of the things that I kept running into while doing the research was life extension, and how there’s so much research into extending life, extending the quality of life, and also ending death. Because, as one of the articles said, there’s a lot of money in extending life, so if you can come up with a way to stop people from dying, you’re the richest people in the world. And you know what? It’s going to happen. We’re going to figure it out. It could come as early as tomorrow, you could look at your news feed and see that, I don’t know, Elon Musk solved the secret of aging, it could be as simple as that, or it could be ten years from now, twenty years from now… but it’s going to happen.

And what does our world look like when we are technically in a mortal species? Of course, the first thing is overpopulation, so how are you going to deal with it? Well, there are multiple ways of dealing with it, most of which are dystopian; I didn’t want that, didn’t want to come up with a dystopian solution.

In Scythe, death is the only thing that’s still managed by humans.

Yes, because the Thunderhead realized it has no right to make that decision; it made the wise choice, as the Thunderhead always does, so it becomes our responsibility. But how are we going to do it in a way that’s not dystopian? Well, that leads me to my solution: the jedi of death.

Even utopia always has to rest upon the shoulders of the people who have to make the choices.

Yes, and there are always difficult choices to be made. And even if you make the right choice, sometimes it’s a very difficult choice, as the Thunderhead comes to realize. It always makes the right choices, but they’re not always easy. Of course, the easiest solution to our overpopulation problem is to find a place to go; it’s to colonize Mars, or colonize the Moon, or be able to send the human race out into the universe. I realized that’s the obvious choice, and the Thunderhead could probably accomplish that; why isn’t it? And then I thought… what if scythes are preventing that happening? Because if we could do that, there would be no need for scythes, they wouldn’t have any power anymore. And so, from the very beginning, I knew that was an important part of the story, but we weren’t going to find that out until book three. But from the beginning, I knew, and I sprinkled in hints from the very beginning, even to the name of the main villain, Goddard. It’s all in there, but if it was too obvious, you would’ve figured it out, and it wouldn’t be as much fun.

Why was it important for you to have a prominent religious leader in book three, The Toll, in a series so focused on science? What is, for you, the connection between science and religion? Do you think people turn to religion when science fails them, and vice versa?

It started with the whole idea that, looking at the things that we will have lost once we become immortal, faith would be a casualty of immortality, because so much of faith is based on the afterlife, it’s based on the fear of death. If we conquer that, then faith would start to fade away. And I thought that faith can be a beautiful thing, just like art. If we no longer have a fear of death, if we no longer have a limited time to live, we may not have the same passion that we have, so art suffers. Looking at all the things that would change, I thought, what if there’s a group of people who are trying to recapture the very idea of faith? But they’re not quite doing it right, because they’re immortal, so they don’t know what it was like to be mortal. So they take bits and pieces of all of this religions and they create their own basically false religion, and then, as has happened with so many religions, they end up being persecuted. Now, from the very beginning we kind of knew that the tonists kind of made up their religion; the irony is that, thanks to the Thunderhead, they’re able to feel as if their religion meant something. So it all came full circle; yes, the tonists’ religion was a false religion, and yet it served the purpose that it needed to serve, and gave its members a reason to be. And as far of the character of The Toll, he knew that he was a false prophet, he knew from the beginning, but he needed to do it in order to help the world. I just wanted to have that look at the idea of the power of faith and how that power can be misused, as in the tonists were a negative force, but also, how it could be positively used.

It started with the whole idea that, looking at the things that we will have lost once we become immortal, faith would be a casualty of immortality, because so much of faith is based on the afterlife, it’s based on the fear of death. If we conquer that, then faith would start to fade away. And I thought that faith can be a beautiful thing, just like art. If we no longer have a fear of death, if we no longer have a limited time to live, we may not have the same passion that we have, so art suffers. Looking at all the things that would change, I thought, what if there’s a group of people who are trying to recapture the very idea of faith? But they’re not quite doing it right, because they’re immortal, so they don’t know what it was like to be mortal. So they take bits and pieces of all of this religions and they create their own basically false religion, and then, as has happened with so many religions, they end up being persecuted. Now, from the very beginning we kind of knew that the tonists kind of made up their religion; the irony is that, thanks to the Thunderhead, they’re able to feel as if their religion meant something. So it all came full circle; yes, the tonists’ religion was a false religion, and yet it served the purpose that it needed to serve, and gave its members a reason to be. And as far of the character of The Toll, he knew that he was a false prophet, he knew from the beginning, but he needed to do it in order to help the world. I just wanted to have that look at the idea of the power of faith and how that power can be misused, as in the tonists were a negative force, but also, how it could be positively used.

The Toll did what he had to do; he was operating under Thunderhead’s orders, which is like God.

If you notice, the Thunderhead made the same choice that God would have made; to realize “I cannot speak with humanity on a daily basis, because the only way they can grow is if they make the wrong choices and I keep my distance”. It’s sort of like when people ask “all these things that go on in the world, how could God allow these things to happen?". I sort of wanted to take the Thunderhead through that process of understanding “I can’t intervene here, because this has to be a learning process of the human species”, and so it was trying to understand the mind of God trough the Thunderhead.

How would Scythe Shusterman glean? What would your scythe name be?

I would be Scythe Vonnegut. Kurt Vonnegut was my favorite writer when I was a teenager and through my twenties. And for my gleaning method, I chose the POV character who became a scythe, Scythe Anastasia. I said “if I was in her position, if I was a scythe, how would I do it?". And it would be what she did; giving people notice, you have thirty days to get your life in order, and you get to choose how it happens. Which, of course, created a turmoil because the scythes are like “you can’t do that!”, but yet the scythe has the right to do it any way that they want. So the way that she does it is probably the way that I would have done it.

How do you choose the scythes’ names?

I have a big spreadsheet. When I first started writing I started going through history and thinking: “What figures from history have contributed to civilization?” Music, art, literature, science, philosophy… And I tried to pick characters that were not necessarily controversial, I didn’t want to pick a character that was a negative character from history. I made a list and then I made sure that that list was evenly divided between male and female and that it touched on as many different cultures and ethnicities that I could, because I wanted to be as inclusive as possible. And then, when I needed a new scythe name, I went down my list and said… not so much “who would the scythe be like”, but “who would this person choose as their model?”. And down to Gleanings, I’m still doing the same things, and throughout the past few years, people have made suggestions, and said “how come you don’t have this scythe, or that scythe?” and I’d be like… “I’m adding that one to my list!”.

Do you think that science fiction is a desire, a promise or a warning?

A little bit of all of it! I think that a lot are cautionary tales, but at the same time, they are stories that show humanity’s ability to overcome the wrong choices that we’ve made, to overcome the problems that we’ve created for ourselves. I don’t believe in stories of futility. Early dystopian novels, many not for teenagers but for adults, are stories of futility. 1984, you know, it’s a wonderful story, I love it, but it’s not a story that leaves us in a good place. I think that, as a writer for teenagers, I have a responsibility to leave them in a better place, to give them something to hold on, to give them sense of hope for the future. And so, I just don’t believe in writing stories of futility. Even if my characters go through very dark and difficult places, it’s only so that they can get through that to a better place, and to accomplish something they couldn’t have accomplished had they not been through that dark place.

Is there anything you can tell us about future projects?

I have a graphic novel coming out that is Holocaust themed, and that one is a very personal project for me, I’ve been working on it for ten years. The art is done by Andrés Vera Martínez and it’s beautiful, the art is fantastic. There is a new mid-grade series, also co-written with Eric Elfman, same exact type of story in that is science fiction, but funny science fiction. I don’t know how they’re going to translate it in Spanish, because it’s a trilogy , and each book is a song title but features an animal. So the first one is I am the walrus, which is a Beatles song.

, and each book is a song title but features an animal. So the first one is I am the walrus, which is a Beatles song.

Don’t worry, you have an amazing translator here, Pilar Ramírez Tello. She’ll come up with something…

Yes, Pilar, she’s fantastic! And what I’m working on while I’m here, during my off-time… I’m working on my next big science fiction series; I can’t talk about it yet, but I’m very excited, very motivated. I was working on four different ideas, and trying to figure out which one I wanted to tell. It’s very rare that I have four ideas for a series that I’m equally as excited about. I started writing all four of them, and one of them just took off, so I said “ok, this is the one.” I wish there were four of me so I could write all four of them!! It’s going to have to be one at a time; but I want to get to the other ones, because I think they’re all really good.

And our last question, could you give us a book recommendation for our readers?

I don’t know if they’ve been translated into Spanish, and they’re not necessarily YA, but a couple of my favorite books that I’ve read over the past year have been This Is How You Lose The Time War (I loved it! As I’m reading I’m thinking “wow, I wish I would have done that”; those are the books that I love, the ones that make me say, I wish I could have done that. And I just read a book by Emily St. John Mandel, who wrote Station Eleven. This is her new one, it’s called Sea of Tranquility, and it’s really well-written, I enjoyed it, I couldn’t stop turning the pages. It’s a time-travel story, similar in some ways to Station Eleven. For YA, one of my favorites was one of the books I read when I was the judge for the national book award, a couple of years ago; it was one the books that I really loved, and it’s called The Way Back, by Gavriel Savit.

Thank you very much for your time!

Thank you!