¿Que te apetece leer?

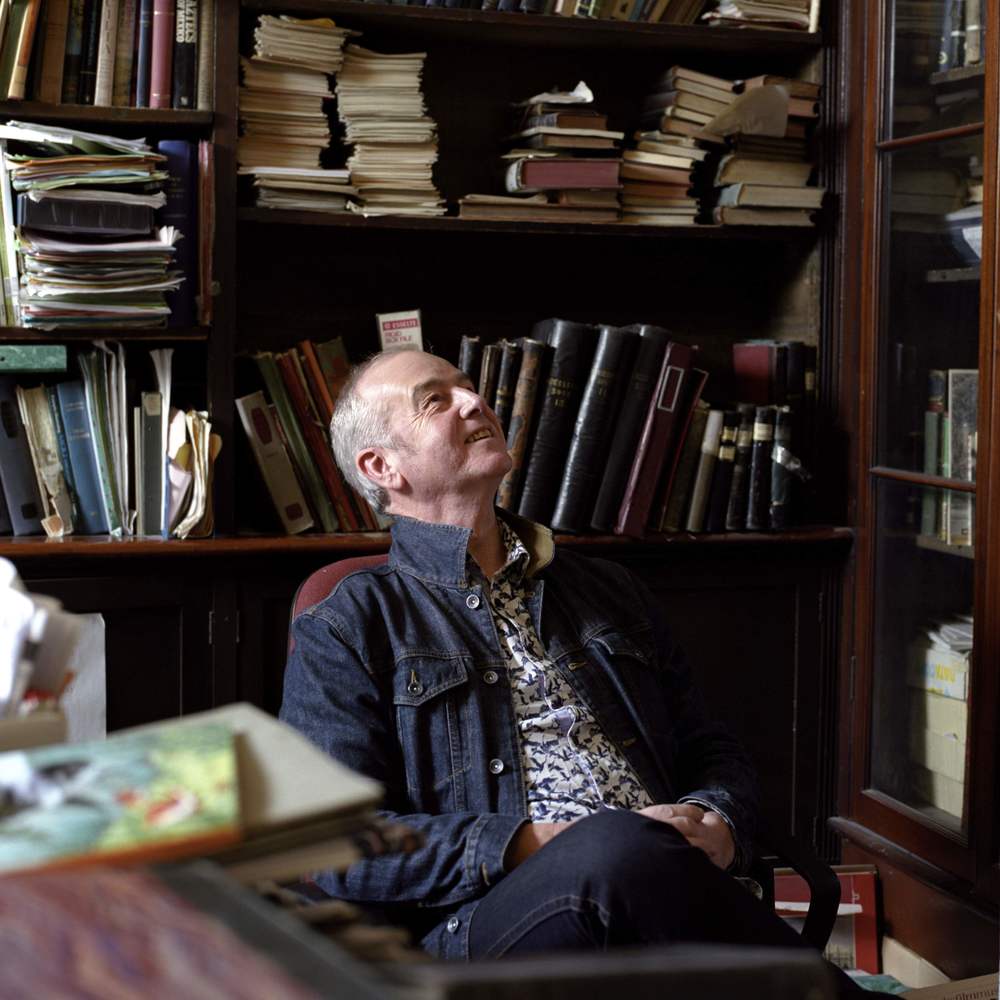

The North of England —more specifically, Northumberland— is a recurrent setting in your novels. As of right now, what is the North for you? And why do you think that distancing ourselves from the place we come from tends to be our first instinct?

The North of England —more specifically, Northumberland— is a recurrent setting in your novels. As of right now, what is the North for you? And why do you think that distancing ourselves from the place we come from tends to be our first instinct?

For a long time, I thought I wouldn’t write about the North, or be a ‘Northern writer.’ I didn’t want to be trapped by my background. I thought I should set my work in some other, distant, imaginary zone. It’s a familiar tale – the teenager/young man who wants to move away from his roots and become something different, something brand new. But I found I was so deeply rooted, there was no way I cast the North from me. Its people, language, landscape, heritage are in my blood and bones and soul. Once I discovered and accepted this, I became both bound and free. I turned back to the North and strangely it became a place that was both entirely familiar and yet still undiscovered. And I began to write in Northern sounds and rhythms. I discovered a kind of poetry and song. And as I wrote, I saw how the real and the imaginary could blend in really thrilling ways for me. The first time I really came to terms with this was when I wrote the stories in Counting Stars, which mingle real and often painful events with events and people that are totally imaginary.

Babies, wings, birds… all of them are common to many of your novels. But why those and not others? Is writing the closest David Almond will get to be a flying bird?

Babies, wings, birds… all of them are common to many of your novels. But why those and not others? Is writing the closest David Almond will get to be a flying bird?

It’s astonishing that we live in a world alongside creatures that are birds, that can leap from the earth and take wing, that can soar as we hope our spirits might soar, that can sing as we believe our voices might sing, that have skeletons that are very like ours, but that are lighter, more flexible, and not earthbound. And they come from a magical object called an egg that contains sticky gloopy stuff that coagulates into bones, feathers, flesh and that becomes a creature that pecks its way out into the outside world. No wonder so many songs, stories, poems are written about these creatures. And one of my most powerful childhood memories is of my mother touching my shoulder blades with her fingers and whispering, “This is where your wings were, David, when you were an angel.” So the sense of my our potential birdlikeness was in me from a very young age. Yes, I do keep coming back to birds in my writing. I guess that maybe I’m trying to use words like songs, or like wings, that might lift me, and perhaps my readers, for a few moments from the earth.

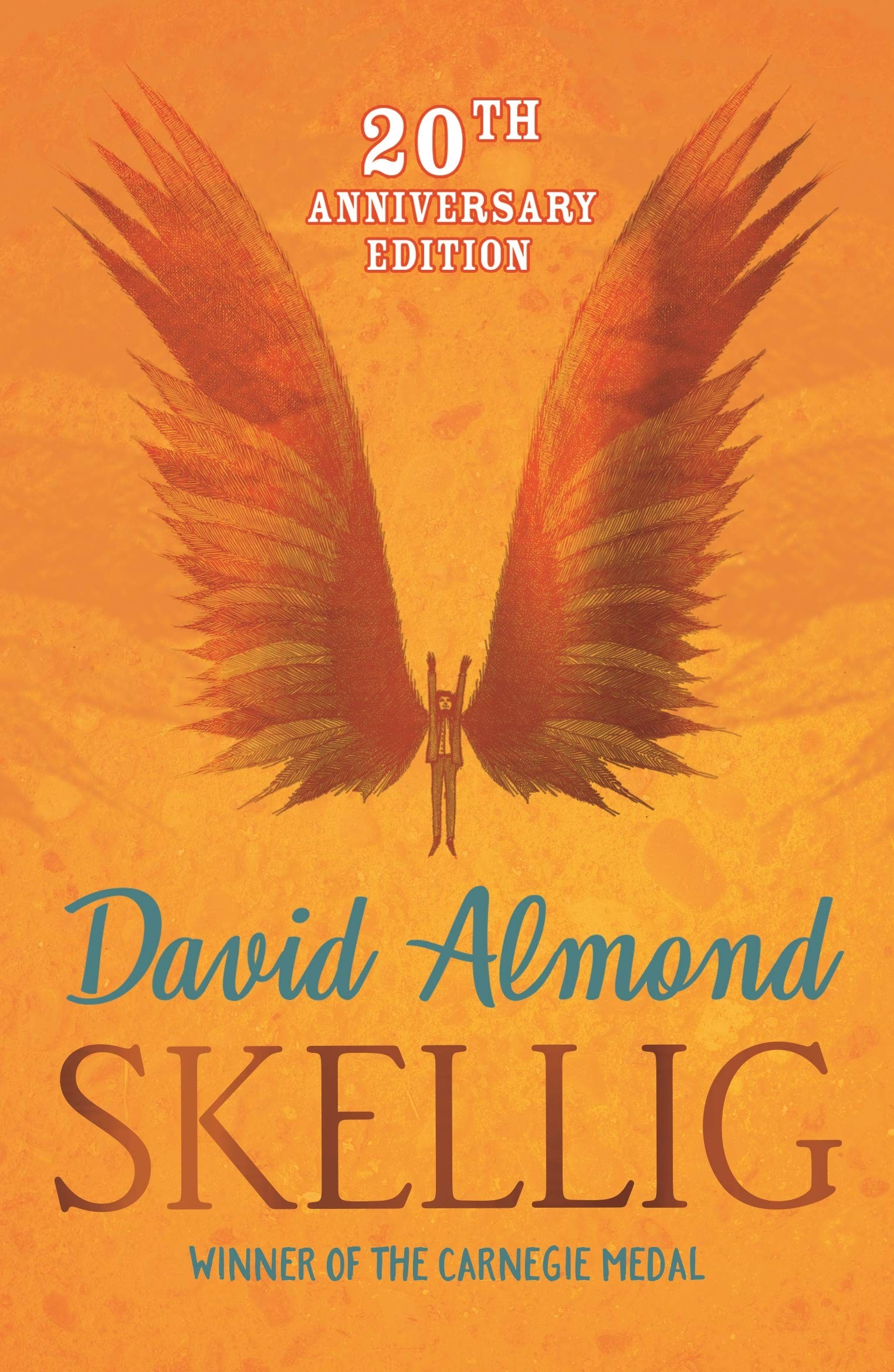

Even though you had been writing for around two decades, your first novel, Skellig, was published in 1998, when you were close to your fifties. What would you say to those who hear the call of writing, but think they have missed their opportunity to become authors?

Even though you had been writing for around two decades, your first novel, Skellig, was published in 1998, when you were close to your fifties. What would you say to those who hear the call of writing, but think they have missed their opportunity to become authors?

Writing is a lifelong journey. You have to write because of the love for it, because you are driven to do it. You can’t really expect wordly ‘success’. I didn’t really mind that it took a long time for my work to take off. I had stories published in small magazines and small presses. I had a few keen readers. I worked hard. I hoped that something big might happen, but I accepted that it might not. I worked as a teacher, and I kept on writing, experimenting. I didn’t try to define too closely what kind of writer I was. I tried to be bold. I never expected to become a children’s writer, but when I began to write Skellig, I suddenly realised that it was a book for the young. I was surprised, excited, liberated. And Skellig became an immediate world-wide success. It led to all the books, stories, plays, songs that I’ve written since and that I continue to write now. Skellig brought about an astonishing change in my writing and my life. I knew that it was important just to keep on working, writing, to accept and enjoy the opportunities that then came along.

What did it mean to you to be awarded the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 2010 and then have the unique prequel of Skellig, My Name is Mina, published a few months later?

What did it mean to you to be awarded the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 2010 and then have the unique prequel of Skellig, My Name is Mina, published a few months later?

I remember the moment when I heard I was to be awarded this. It was as if time stood still. I was astonished and very proud. It felt like an award for all the hard work I’d put in. It was also an award for those who had believed in me, who had published me, who had read me. And My Name is Mina, published so soon afterwards, felt part of it. In so many ways, Mina expresses and embodies my own thoughts, dreams, yearning. I was so pleased that such an experimental, playful book was published with my name on the cover.

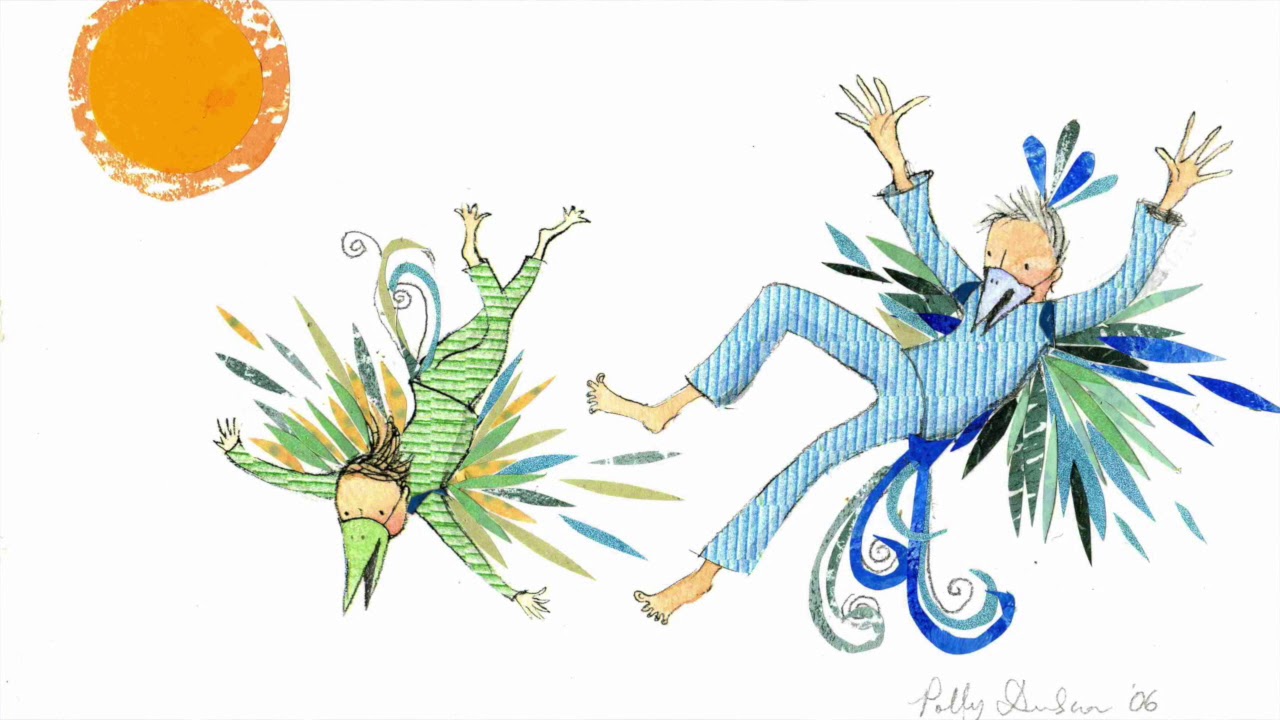

My Dad’s a Birdman was your first children’s book with illustrations and, in fact, it initially started life as a play. Having had written a few more of those since then, what makes a children’s book a good and true children’s book for you? How well do they translate into theatre?

Yes the books started life as a play. Creating it for the stage, and then actually seeing it on stage, helped me to imagine it as an illustrated book. When I rewrote it as a novel, I was aware of leaving imaginative space for an artist, just as I had left imaginative space for director/actors/designer etc. It was a new kind of collaboration. I wrote the novel when my own daughter was about 8 years old. It was clear to me that some people thought that by that age, children should have no more need of pictures in their books. I totally disagreed with such an attitude, of course. So I was determined to create my first illustrated book for my daughter and for children of her age. I loved seeing the wonderful illustrations by Polly Dunbar. She brought her own vision, recreated my story, gave it a new kind of vivid life. Several of my books have now been adapted for stage: Skellig, The Savage, The Boy Who Climbed Into the Moon, A Song for Ella Grey, Heaven Eyes, Secret Heart. A story on the page can look finished, but they don’t keep still. Stories keep on reshaping themselves in the reader’s mind, and often they are reshaped into stage plays. It seems a natural process to me. Stories are living, evolving things. Since My Dad’s a Birdman, I’ve written many books in collaboration with wonderful artists. This for me is one of the joys of working in the children’s book world. ‘Adult’ authors are not given the same kind of opportunities.

For years, metafiction has been present in your novels —as it is the case of The Boy Who Swam with Piranhas or The Savage—, and you have made use of various narrative voices and forms. In which ways have all these narrative techniques helped you explore the line between reality and fiction?

All stories exist in a weird and wonderful space between the real and the imagined. It seems natural to me to explore that space, and to experiment within it, and sometimes to make the strangeness of it explicit. And of course the weirdness doesn’t apply only to stories or to art. Life is weird, the word is weird, we are weird. We are all both real and dreamlike. I think that children understand this. They’re quite capable of seeing it explored in their books.

All stories exist in a weird and wonderful space between the real and the imagined. It seems natural to me to explore that space, and to experiment within it, and sometimes to make the strangeness of it explicit. And of course the weirdness doesn’t apply only to stories or to art. Life is weird, the word is weird, we are weird. We are all both real and dreamlike. I think that children understand this. They’re quite capable of seeing it explored in their books.

Many of your protagonists are struggling, yet hopeful children. In your opinion, how much has the experience of childhood and teenage years changed in the last decades? And what do you think young people have to learn to navigate this terrifying and wonderful world we live in?

Yes, the world is both terrifying and wonderful. The terrors now do seem to be extreme – pandemic, inequality, climate change. In essence, children don’t change. The drama of being born, growing up, remain the same.

There are echoes of war in several of your novels (The Fire-Eaters, Jackdaw Summer… even in Bone Music). There is also the figure of “the other” as an enemy, but also the idea of redemption. Why do you think important to write about war?

War is horrible, but it’s always there, somewhere in the world. I grew up as the world we were recovering and rebuilding after WW2. My dad had fought in Burma. There was evidence of the war all around. And as I grew up, there was the constant fear of a nuclear war beginning. And there was Korea, and Vietnam. War never goes away. More recently: Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan. And there seem to be people who want war, who welcome it. It says something about we human beings. We have benign ambitions, we want to create a better more peaceful world, but there’s something in humanity that seems to want disturbance and destruction. The very act of writing is an act of optimism and creativity, a move against the forces of destruction. Maybe children’s writers feel this most intensely. Every new child, every new story, is a chance to make things better. I find myself being drawn back to writing about war – I have to show how awful it is, how it draws people to it, and I have to show that there are better, more creative ways of being, to try to show that we can move beyond the destructive forces in ourselves, that love is stronger than violence.

War is horrible, but it’s always there, somewhere in the world. I grew up as the world we were recovering and rebuilding after WW2. My dad had fought in Burma. There was evidence of the war all around. And as I grew up, there was the constant fear of a nuclear war beginning. And there was Korea, and Vietnam. War never goes away. More recently: Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan. And there seem to be people who want war, who welcome it. It says something about we human beings. We have benign ambitions, we want to create a better more peaceful world, but there’s something in humanity that seems to want disturbance and destruction. The very act of writing is an act of optimism and creativity, a move against the forces of destruction. Maybe children’s writers feel this most intensely. Every new child, every new story, is a chance to make things better. I find myself being drawn back to writing about war – I have to show how awful it is, how it draws people to it, and I have to show that there are better, more creative ways of being, to try to show that we can move beyond the destructive forces in ourselves, that love is stronger than violence.

Brand New Boy and Bone Music are your latest novels. We’d dare to say that they are two new masterpieces of yours, proving that your writing is in perfect shape. What can you tell us about what’s coming next?

I’ve just finished a new novel called Puppet, probably out in ‘23. Before that, I have a couple of picture books coming out: The Woman Who Turned Children Into Birds (illustrated by Laura Carlin); A Way to the Stars (illustrator to be decided); Paper Boat, Paper Bird (illustrated by Kirsti Beautyman); a new edition of the short novel, Island, this time with illustrations by David Litchfield. There will also be a new illustrated edition of Skellig to mark its 25th anniversary in 2023!

The idea of hospitality is explored both in Brand New Boy and in Bone Music, and while the idea of “rewilding” is already in the former, it will fully take the spotlight in the latter. How many of our current problems do you think come from neglecting these aspects?

I think we have over-controlled and over-mechanised the world and ourselves. The natural world needs to be freed from our desire to control and reshape it. This becomes more and more obvious as time goes on. Children need to be allowed more imaginative freedom, to be allowed to be themselves, to grow organically. In Bone Music, Andreas says, ‘Beware the adult who wishes to regiment the young.’ There are too many adults who wish to do this. Our education systems, as designed by politicians who seem to have such a narrow vision of what a human being might be, are too structured, too rigid, too mechanistic. There are wonderful schools and teachers, and children themselves of course are dynamic agents of creativity and growth, but their opportunities are curtailed. We need change.

Thank you so much, David. It was a pleasure talking to you.

Thank you so much for inviting me to take part in this interview - and thank you for such perceptive and thought-provoking questions! It is a real pleasure and privilege to be in touch with my Spanish-speaking readers. Hello to you all. Best wishes, and happy reading!